MY ART PHILOSOPHY....

Beauty

Since the beginning of humankind, we have struggled, among other things, with the definition of beauty. Different eras and different philosophers had their own ideas, yet no one was able to agree

upon one single idea. The only thing that seemed consistent without being too cliche, was that “beauty was in the eye of the beholder.” Today considered, everyone still has their own meaning. A

mother may find

her child with mud streaked across its face beautiful, where you see a mess. A scientist may find a certain mold beautiful, but you would look at it in disgust. Despite the differences in people’s

opinions it is important to explore their ideas in order to get a firm background on

what beauty could be and what it is in your mind. Is it all appearance?

Is it perfection? Is it what you are told?

In the earliest times, it was Socrates that first explored the definition of beauty, he felt that aesthetics was a form of purity. Things that are pure within themselves evoke pleasure, thus beauty. Socrates’ idea can be considered as a form of beauty, yet is far from the whole spectrum, it is not restricted to such a narrow theme. Plato was another mind in great interest in trying to pinpoint the role of beauty in society. Plato believed, among other things that relative beauty only exists when you compare objects to each other. If some aspect of an object is beautiful, the whole object is beautiful. After further consideration, Plato came up with the most logical of all the philosophies, that beauty cannot be defined. Some things have the “ideal beauty” and no one can consider them not beautiful. It is also in agreement with Plato throughout the time that beauty provokes pleasure. Following in the ideas of Plato, Plotinus also

preached that there is no one object that beauty can be defined as nor is there one aspect of any object that beauty can be defined as. He also believed that “beauty is that which irradiates

symmetry rather than symmetry itself.” Plato created a trend in that beauty cannot be defined, yet philosophers continued to struggle with the meaning. Aristotle hypothesized that the senses most

prone to recognizing beauty are sight and hearing. The eighteenth century had philosophers such as Locke and Burke who made the comparison between sublimity and beauty. Locke believes that sublimity

and beauty are not alike because sublimity creates feelings of wonder and awe, and beauty creates feelings of joy and cheerfulness. Where Burke said that beauty calms one, while sublimity intensifies

one’s emotions. Something can be ugly and aesthetically appreciated at the same time. In the same century, there was Hutcheson thought that “The word beauty is taken for the idea raised in us.” There

was Alison also in the eighteenth century who took off on Plato’s ideas and said it was impossible to find

a common property that all beautiful things contain. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries were the first to try and define beauty scientifically.

Laws were attempted to be constructed that could be applied to the definition of beauty. It was discovered that this method was too restricting and many scientists soon gave up on the idea

altogether.

Beauty was later defined as a “term of approbation”, or a value, or higher stature, as opposed to “pretty”. In the end, the only thing that remains consistent through time in philosophizing beauty

was that it was indeed too broad to define. What everyone agreed upon was that it is impossible to find a common property that all beautiful things contain and that it is impossible to define.

Beauty II

The concepts of beauty were first described by the ancient Greeks. Beauty was a narrowly defined and central concept for the Greeks. The classical values stressed order and serenity. As time went on,

the concept of beauty became less central and is now called aesthetics.

Today, the aesthetic notion of beauty is vague and subjective. We can see how the concept of beauty developed by tracing its historical roots.

Classical Aesthetics

Aesthetics refers to beauty in an object. The Greek philosophers Plato and Socrates were the first at attempting to define beauty. They thought of objects or nature as being inherently beautiful:

beauty is inside an object. In all attempts to define the characteristics of a beautiful thing they focused on simplicity and symmetry. Beauty is perceived through sight and hearing. Beauty is not

relative, objects cannot be

compared with one another. The beauty within an object is its pure and ideal beauty. This definition restricted objects that could be beautiful, such as paintings, tragedies and comedies, and living

creatures. Beauty is excellent, perfect, and satisfying. The concrete and simple Greek concept of beauty were enlarged by Plotinus. He rejected beauty as being merely a formal property. He describes

beauty as not just symmetry, but rather as a quality that “irradiates” and moves us. Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, beauty was an object property that could be defined by rules. A person’s

response to beauty could be described as “pleasure” but the observer’s reaction did not define what was considered beautiful.

The Eighteenth Century

In the 18th century, the broader concept of aesthetics was first established by British philosophers. Art and beauty were now defined based on the experience of the perceiver. That is, beauty is in

the eyes of the beholder. John Locke’s “Essay” describes the concept of the sublime; “amazement” and “awe” as contrasted with the concept of beauty, which is described as “joy” and “cheerfulness.”

Edward Burke

added to this contrast, characterizing the sublime as “terrible” or emotionally intense. This is compared to beauty, which he described as pleasurable and relaxing. These two experiences are

incompatible with each other. Burke went as far as to include ugliness in sublimity. He included a great diversity in the subject matter as qualifying for the sublime. 18th-century

philosophers, such as Francis Hutcheson,

struggled with an inherent dilemma in their concept of beauty. If beauty is based solely on the response of the perceiver, how can this response be documented or observed? They wanted to find a link

between the classical concept of an observable property, like uniformity, and the unobservable property of evoked experience.

The 19th and 20th Centuries

The 19th and 20th centuries have seen a change in the view of aesthetics, due to attempts to analyze beauty scientifically. Experiments have tested the total experience of beauty and looked at the

levels of appreciation it arouses in terms of pleasure and displeasure. This approach has provided more conflicts than answers, however, as it does not take into account objective views and other

factors related to

the perception of beauty. The present century has tried to draw a distinction between beauty when it implies the total aesthetic value of an object and when it represents only one aspect of an

object. The first meaning gives an object, like a sculpture, a total value of its beauty, relative to the sculptures around it. The value represents the entire object and its experience as a whole.

The second meaning looks at the characteristics of an object to determine its beauty, such as symmetry. It values these classed types of beauty, rather than the entirety of an object.

Anyone Creating Any Type Of Art Should Try To Aim High...GOOD ART

Good art is positive.

Good art talks not just about problems but offers solutions.

Good art reaches the best of human emotions.

Good art makes you feel good - about yourself, about life, about the world.

Good art is realistic and positive.

Good art shows how we can make things better, in a real way.

Many people don't know how, so artists must show examples of how it could be.

Good art is peaceful and harmonious.

Good art makes you want to be a better person, it makes you want to look positively upon the world, it makes you want to make a difference in the way you live and makes your outlook richer.

Good art teaches. It teaches truths of life, of the soul.

It teaches how we should be in an ideal world.

Art is Personal Expression...

Art is about personal expression. It is about the life, the emotions, the thoughts, and ideas of the artist. It matters very little what observers do, their activity is not required, only their appreciation. The practice of Art doesn’t require them. It is a necessary activity for the artist and the artist alone.

GOOD ART...BAD ART.....THE TRUTH!

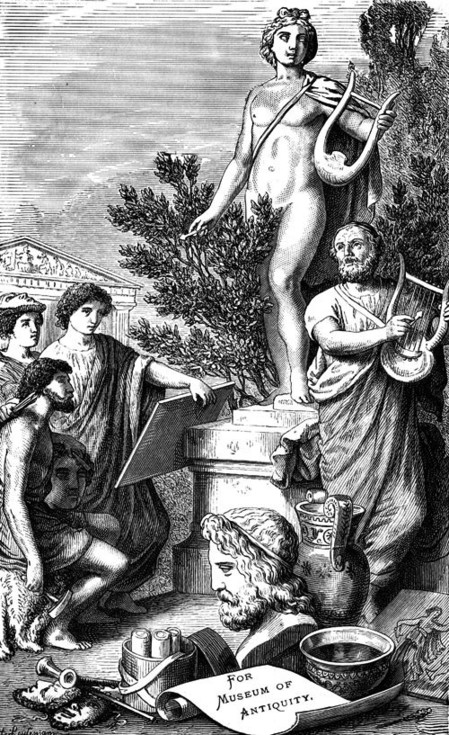

The art of painting, one of the greatest traditions in all of human history has been under a merciless and relentless assault for the last one hundred years. I'm referring to

the accumulated knowledge of over 2500 hundred years, spanning from Ancient Greece to the early Renaissance and through to the extraordinary pinnacles of artistic achievement seen in the High

Renaissance, 17th century Dutch, and the great 19th century Academies of Europe and America. These traditions, just when they were at their absolute zenith, at a peak of achievement, seemingly

unbeatable and unstoppable, hit the twentieth century at full stride, and then ... fell off a cliff, and smashed to pieces on the rocks below. Since World War I the contemporary visual arts as

represented in Museum exhibitions, University Art Departments, and journalistic art criticism became little more than juvenile, repetitive exercises at proving to the former adult world that they

could do whatever they damn well wanted ... sadly devolving ever downwards into a distorted, contrived and contorted notion of freedom of expression. Freedom of expression? Ironically, this

so-called "freedom" as embodied in Modernism, rather than a form of "expression" in truth became a form of "suppression" and "oppression." Modernism as we know it ultimately became the most

oppressive and restrictive system of thought in all of art history.

Every reasonable shred of order and any standards with which it was possible to identify, understand, and to create great paintings and sculpture, was degraded ... detested ...

desecrated, and eviscerated. The backbone of the painters' craft, namely drawing, was thrown into the trash along with modeling, perspective, illusion, recognizable objects or elements from the

real world, and with it the ability to capture, exhibit, and poetically express subjects and themes about mankind and the human condition and about man's trials on this speck of stardust called

Earth ... Earth, hurtling through infinity with all of us along on board, along with everything we know and everything we hold dear. The reason... philosophy ... religion ... literature ...

fantasy ... dreams, and all of the feelings, emotions, and pathos of our everyday lives ... all of it was no longer worthy of the painter's craft. Any hint by the artist at trying to portray such

things was branded as banal, maudlin, photographic, illustration, or petty sentimentality.