THE STILL LIFE....

The Still

Life: Social Economic Background

The creation of the Dutch Republic gave rise to great pride in national identity and with it came a delight in the new art that was uniquely Dutch. As the economy flourished, and trade with the

Indies and South America expanded, so did the fashion for collecting, the popularity of painting in general, and Still Life -Stilleven -in particular. Watchful Calvinist ecclesiastics, dwindling

royalty, and powerful Burghers changed the face of patronage. With the emergence of the aspirational, property-owning bourgeoisie, a whole new market opened up.

Origins and Definition of Still Life

As a result of this trade with far-flung places and the introduction of exotica, Dutch artists of the 17th Century became renowned for being greatly concerned with what Kahr refers to as a: ‘close

scrutiny of the natural world. This, combined with their preoccupation with perspective and the study of light, provided the basic elements of Still Life painting. The term had come into general

usage in mid-century, Still Life being the carefully composed portrayal of inanimate objects. Living creatures were in fact allowable as long as they were incidental to the main theme. Specialization

was a notable feature of Dutch 17th-century art; consequently, Still Life - itself a particular aspect of art - further diversified into different categories.

The Distinct Categories

The earliest examples, from the beginning of the 1600s and later influenced by 'tulip-mania', were the popular floral paintings; these were followed by flowers with fruit, then the humble 'breakfast

pieces'. As the century progressed, and wealth became widespread, so the 'breakfast' developed into the 'banquet piece'. Perhaps influenced by deep-rooted Calvinism centered on Leiden University, the

Dutch psyche remained a moralizing one and the concern with the transience of life was the motif of the numerous 'Vanitas' paintings and an element in other genres. Another important facet of Still

Life, Trompe L'Oeil - French for 'deceive the eye' - evolved in mid-century from the game piece, its illusionism appealing to the Dutch penchant for humor. Finally, in the latter part of the century,

taste changed, color and form became more baroque and pronk still life- the art of the ostentatious - was born.

Flower Pieces

Just as painters specialized in different aspects of art, certain towns became the focal points noted for specific genres, and Middelburg, Utrecht, and Amsterdam were the main centers for flower

painting, a genre that was highly regarded and well paid. The artists, although portraying genuine flowers, depicted them in impossible arrangements: blooms from all four seasons were shown at once,

reflecting the studio practice of painting individual flowers, in season, as studies for future reference. Flowers were accurately detailed without the overlapping that would happen naturally in a

vase arrangement. Another artifice, in the 1620s, was the image of a snail, or butterfly flying in the background, which referred to the soul, freed after death. Flowers were ciphers for spring but

there was also an evolving symbolism in the language of flowers that was accessible to contemporary viewers: the Madonna lily, for instance, was an attribute of the Virgin Mary, the white iris a

symbol of her purity, and the rose, her love. A daisy meant charity, a buttercup the unmarried state, and the sunflower represented the love of God, or sometimes, earthly love.[2] Some artists

presented their work as so-called 'niche' paintings (in emulation of Trompe L'Oeil Roman murals), which emphasized the symmetrical aspect of the arrangement. An excellent example is the Middelburg

painter Ambrosius Bosschaert's Vase of Flowers of 1620 (oil on panel, 64 x 46cm, Mauritshuis, The Hague) whose Wan Li Vase refers to oriental travel, and fallen flower-head to decay and transience;

the flower, however, is a carnation - the symbol for resurrection and eternal life.

Fruit with Flowers

Symbolism was present too, in the exotic fruits and shells brought back by trading merchants. Shells had particular appeal to a nation governed by the sea and, with fruit, were often displayed as

part of floral compositions. Opened - as in the case of oysters or mussels - they suggested vanitas overtones of the brevity of life or could be interpreted as having erotic implications. On a higher

level, the fruit had a religious message: the apple of temptation, the grape the blood of Christ; in the words of St Thomas Aquinas; ‘a corporeal metaphor of things spiritual;’ and a different shell

might represent each continent as a visual tribute to the exploratory travel and scientific discoveries of the day.

Breakfast Pieces

With the introduction in Haarlem and Amsterdam of the Ontbijtje, the Breakfast Piece, the format changed to landscape to accommodate the expansion of a tabletop. Placing the table edge parallel to

the horizon, with the table cover dropping markedly downwards, enhanced the impression of space. The food illustrated was basic - bread, cheese, fruit, nuts, herring - and often presented half eaten

for realism. The cutlery and dishes of pewter or pottery were equally simple but skilfully painted. In earlier breakfast pieces, the viewer is looking downwards onto the table, but as the century

progresses, the viewpoint is lowered. Like the flowers, the objects were carefully spaced and by the 1620s were projecting over the table edge, creating an illusion of nearness to the viewer. By the

1630s these bright colors were becoming more monochromatic.

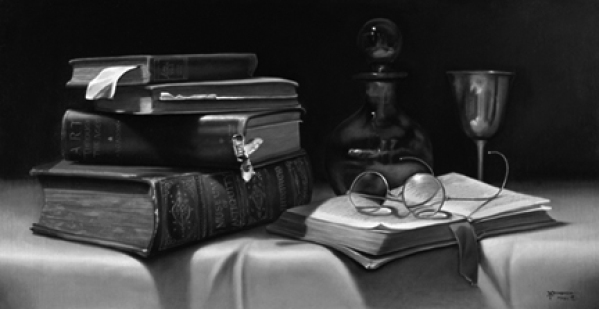

Vanitas

Paintings - A Metaphor for Transience

Society's awareness of death did not disappear with the end of the Twelve Year Truce; in the 1620s the Republic suffered two outbreaks of Bubonic Plague and this may account for the proliferation in

Leiden of Vanitas paintings, whose recurring motif, the skull, was a constant reminder of mortality. Symbolism was present in every form of Still Life but never more significant than in Vanita's work

where everything spoke of ephemerality and the inevitability of death: the watch or hourglass - the passage of time; the overturned glass - the emptiness of life; a violin - the vice of enjoyment, or

music fading away; a book - pride in knowledge - an artificial virtue, or history being finished; a smoker's empty pipe, a guttering candle or smoking oil lamp - life is eventually snuffed out; and

airborne soap bubbles were evanescence epitomized. However, there remained a redeeming Christian reference, the chaplet of corn on a skull, a reminder of the Resurrection. Fuchs suggests that this

density of morbid symbols would have appealed to the intelligentsia at Leiden University, the center for the study of Calvinism.

Trompe L'Oeil and its Relationship with the Game

Piece

Perhaps to counter the sobriety of the Vanitas paintings, a new category of still life appeared in the 1640s, the amusing, illusionistic game piece. Hunting being an intrinsic part of Dutch life, the

gentleman-hunter was a valuable client, yet the game piece is a relatively late arrival on the scene, although there were earlier precedents. The game would have been hung in many Dutch kitchens; the

artifice of the game piece, therefore, was to present an apparently real bird into the room: a two-dimensional object is 'modeled' to convince the spectator of its three-dimensionality as a 'vehicle

for persuasion and challenge'.[4] Effective imitation of reality became a benchmark of the artist's virtuosity and Melchior d' Hondecoeter achieves this humorously by the addition of a child's chalk

graffito on the board his thrushes are hanging from in his Trompe L'Oeil with Dead Birds on a Pinewood Wall, (oil on canvas, 84 x 66cm Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, Aachen). The first mention of the term

Trompe L'Oeil in print was not until 1800 when the work of one Louis-Léopold Boilly was thus described in the catalog of the Paris Salon of that year. The earliest example of a '3 D' game piece is

thought to be Jacopo de' Barbari's painting of a partridge, Still Life, (oil on panel, 51.6 x 42.4cm; signed and dated 1504, Alte Pinakothek, Munich); however, the puzzling inclusion of armored

wristlets suggests that it may actually have been an emblem painting for a member of the nobility.

The

Origins and Branches of Trompe L'Oeil

Led by two of Rembrandt's pupils, Samuel van Hoogstraten and Carel Fabritius who were concerned with illusion and perspective, Dutch Trompe L'Oeil was probably derived from the Italian marquetry of

the Quattro-cento; Venetian intarsia, where whole rooms were paneled with 'mosaics' and 'frescoes'. The Italians in their turn were inspired by Classical Roman villas. Artists visiting Italy would

have brought these ideas back to the Netherlands. Certainly, both Trompe L'Oeil and game were depicted in the art of ancient Greece and classical Rome: Pliny the Elder records in his Natural

Histories the famous confrontation between two Greek 5th Century BC painters, Zeuxis and Parrhasios. Zeuxis portrayed grapes so skilfully that birds flew down to eat them. In response, Parrhasios

painted a picture concealed by a 'curtain', which Zeuxis attempted to open. This incident set the precedent for the 17th-century illusionist 'curtain' paintings, a motif, which along with

chantournés, 'niche' paintings, game pieces, hunting gear, letter racks, quodlibets, cupboards, easels, and peepshows comprised Trompe L'Oeil.

Curtain Paintings

Centered on Delft, Leiden, and Amsterdam, curtain paintings were of two types: the draped theatrical 'swag' pulled to the side or sometimes knotted up, and the curtain suspended from a rod running

parallel to the frame (itself often an illusion). They were usually painted in blue or green and were possibly popular because the Dutch often protected their actual paintings behind curtains. A

self-portrait by Cornelis Bisschop (Dordrecht 1630-74), wittily depicts him challenging the viewer by holding back a curtain to reveal a hidden picture, an implied homage to the Zeuxis story. The

curtain motif, originally introduced by Rembrandt (Holy Family, 1646, oil on panel, 46.5 x 68.5cm, Kassel, Staatliche Museen), was broadly applied in the 1650s and 1660s, from genre paintings by

Gerrit Dou, to church interiors by Emanuel de Witte. Koester nominates Trompe L'Oeil: Still Life with a Flower Garland and a Curtain 1658 (oil on wood, 46.5 x 63.9 The Art Institute of Chicago) by

Adriaen van der Spelt and Frans van Mieris, as the outstanding example.

Chantournés and Easels

Cornelis Bisschop originated the 'Chantourné' piece where a fretsaw was used to cut out a work - in wood or canvas - in curved outline, before placing it in its 'natural surroundings. From this,

developed the 'Easel' paintings, where the entire cut-out' easel' complete with attached works in progress, was an illusion.

Letter Racks, Quodlibets, Cupboards, and

Peepshows

Samuel Hoogstraten was the witty initiator of the Porte letter, the letter rack, a few red ribbons pinned to a board and containing snatches of socially informative letters, a motif that possibly

derived from the Italian signature Cardellini. The Quodlibet, Latin for 'what you like, was a letter rack also holding personal items found in any study: combs, scissors (both Vanitas emblems), pens,

bills, etc. Some quodlibets were displayed under a 'curtain', thus becoming double deceit. An extension of this specialty was then to paint the cupboard onto which the letter rack was attached,

complete with metal hinges, locks, and handles. The experiments with the impact of perspective on the eye culminated in the so-called 'peepshows'; these were boxes with complex, curved interiors of

houses, churches, etc.

Trompe L'Oeil with Hunting Equipment

Working in the latter half of the century for the bourgeois hunting market, two little-known illusionist painters thought to be brothers, developed a highly specialized facet of still life. These

were Anthonie and Johannes Leemans whose focus was not the hunt, nor the trophy, but the actual implements involved in trapping and killing the game. Produced as 'over-doors', their Trompe L'Oeil

paintings provided the would-be hunter with his equipment, apparently hanging ready for use. Hunting gear, without a game, was also painted by Philip Angel and Cornelius Biltius.

Pronk: Sumptuous Art

As the century progressed and wealth increased, flourishing households acquired exotically beautiful materials and artifacts. This affluence was reflected in their paintings, which used expensive

pigments such as lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, and which, because of the detail involved, were labor-intensive, hence costly. Fine silverware, Venetian glass, oriental rugs, and ginger jars

abounded. This luxury and opulence are epitomized in Willem Kalf's Still Life with a Late Ming Ginger Jar, (1669 oil on canvas, 77 x 66.5cm, Indianapolis Museum of Art). Even the frames became gilded

and elaborate, rather than black and simple as previously.

By the 1640s this new lavish ornate-ness had transformed the humble breakfast piece into a banquet. The food, no longer simple but including imported, expensive fruits, and lobsters not herring, was displayed with the finest tableware and glass, exemplified by the works of Abraham van Beyeren. However, the vanitas element remained a warning against over-indulgence: the ivy signifying resurrection, the bread, and wine, the Eucharist.

Luxury even influenced the portrayal of game pieces. The somber palettes were replaced in the 1660s by gorgeous blues and reds; hunting bags were velvet and hunting horns hidden behind a flurry of feathers, as in Willem van Aelst's Hunting Still Life.

The Survivors

17th Century Still Life encompassed an enormous artistic range that peaked by the 1670s and seemed to stagnate thereafter, perhaps because of the deaths in the 1680s and 1690s of so many of its

exponents. What did survive, were the two aspects entrenched in the Dutch psyche: decorative hunting still lifes and the flower paintings.